The BLOG section is a space for sharing a wide range of content—from philosophical and aesthetic reflections, reviews, and work-in-progress notes to practical resources such as instructional videos, code, and literature.

The review of Hong Kong New Music Ensemble's season opening concert on August 16th 2025 in Freespace, Kowloon West is out! You can read it below.

The Review

Opening their new 2025/2026 Season with the initiative GAME/PLAY, the Hong Kong New Music Ensemble (HKNME) seems determined to highlight the fun side of so-called new music. As their recently appointed Director of Programming Daniel Lo explained in his opening remarks, contemporary music is still too often perceived as overly serious, too heavy for an “average” listener. And who better to invite for such an occasion than the European contemporary music star Simon Steen-Andersen: a composer known for his transdisciplinary flair, his mischievous collisions of performance and theatre, and his uncanny ability to surprise through the joyous intersections of sound and vision. Whether in RunTime Error, where he gleefully uses a joystick to play two juxtaposed videos of himself running around a theatre, knocking objects over back and forth, or in his Piano Concerto, where a live pianist is set against a recording of a piano being dropped from a ceiling and smashed to pieces, Steen-Andersen’s work embodies humour and playfulness. A perfect match, then, for GAME/PLAY.

It was a true delight to enter Freespace, Hong Kong’s largest black box theatre (and arguably among the largest in Asia), its central seating area filled to the last chair: a sold-out show. This in itself was an outstanding achievement for a contemporary music concert, especially in August, when anyone who can usually escapes the endless storms and humidity of the Hong Kong summer. The stage set-up mirrored the program’s ambitions, a unique ambisonic disposition with roughly five musicians on each of the left and right walls, another five in the back, and a massive projection screen at the front facing the audience.

The concert began with the premiere of Antiphon, a work for 14 instruments by Daniel Lo, with live-processed visuals by his artistic partner, Yu Wing-yan, an experimental videographer who blends various visual genres and with whom he had already collaborated back in 2017. In keeping with the new season’s theme, and clearly resonating with the work of his esteemed guest Simon Steen-Andersen, the curator presented his own new piece that explored, as the program note put it, “the relationship between the music produced and the musicians’ performing gestures, as well as the connection between the audience’s sonic and visual experiences.” That description, if somewhat schematic, was in fact a fair summary of what unfolded.

The piece opened softly: two high strings in pizzicato, moving in contrary motion from unison to octave and back again, as if delineating the passage of time, almost like a rusty clock that intermittently ticks and stalls. Their fragile dialogue was punctuated by a sudden flurry of repeated notes played by individual brass instruments, which seemed to mask the subtle entry of new instrumental pairs, each joining the pulsing texture at the end of a crescendoing gesture. Suddenly a tutti swell broke through, landing on a downbeat, only to dissolve just as quickly. The process then restarted, like a slow unveiling, always with a subtle variation. Lo guided us almost didactically, gradually bringing each instrument into focus, and linking it to a simple geometric figure in Yu’s video: each shape distinct in colour, fixed in position, its pulsing intensity mirroring the rhythmical gesture of its musical counterpart. The first was a circle for the trumpet, later came triangles, ellipses, rhomboids, scattered across the screen like glowing glyphs.

I found it fascinating how the “movement” of these icons (which was not actual movement but a play of hue and brightness) corresponded to instrumental tuplets, triplets, quintuplets, sextuplets. Only later, in discussion with the artists, did I learn that each icon was generated from the live microphone signal, its intensity linked to the sound’s volume. As the piece progressed into its second third (around its golden mean), longer sustained notes appeared, still in short contrary sequences, and the density of instrumental pairs increased. These groupings of two, four, or six created a thicker sonic presence, mirrored visually as shapes began to overlap, cluster, and intermingle, forming an image faintly reminiscent of a schematic map of a city. Despite frequent hints of an impending climax—gestures swelling toward a common downbeat—the tension was never fulfilled. There was only one true tutti, quickly dissipating, and towards the end the music returned to its opening logic: counterpoint in pairs, punctuated by percussive gusts, only now softened into string harmonics and airy brass sounds. The piece closed with the same clipped interruptions that had defined it throughout. The players of HKNME proved themselves masters of performance in such a barren landscape, which could easily have fallen flat were it not for their expertise in generating nuance within the limited space of overwhelmingly soft and fragile sonorities.

What struck me most was the blend of simplicity and complexity, novelty and tradition. Complexity arose from the layering of many simple strands, simplicity, rooted in tradition, was found in the visual idiom itself: rudimentary shapes and bold colours that evoked early 20th-century Italian Futurism, especially when the screen became overfilled and plastered with icons. At the same time, this vocabulary resonated with contemporary culture, reflecting our everyday language of emojis, avatars, virtual masks and filters. It reinforced the idea that novelty is always relative, what feels new depends on what we have previously encountered.

Yet my subconscious evocation of early 20th-century aesthetics was no coincidence, sparked not only by Yu’s images. Lo’s filigree textures, more concerned with voids, chamber-like dialogues, and intervallic relationships than with full tutti or extended techniques (pizzicato and half-air sounds hardly counting as such), echoed Anton Webern, a contemporary of Futurist painters like Giacomo Balla and Ivo Pannaggi. Just as Webern was meticulous in his structures, so Lo never strayed from his concept of “anti-phon,” guiding us through his lacework of instrumental pairings in anti-parallel motion, always disrupted by short percussive gusts. This logic was doubled in Yu’s video, where icons too began to misbehave in agglomerations, disrupting the clean geometry of the system.

Now, it is rarely a good idea to compare one artwork with another. Yet given that the program note explicitly framed Antiphon as a kind of homage to Black Box Music, the temptation was too strong. Knowing some of Lo’s previous output, it was slightly surprising that he chose to work so directly with an audiovisual dynamic, terrain that is more Steen-Andersen’s strong suit. That is not to say Lo has never embraced multiple disciplines. His chamber operas A Woman Such as Myself and Women Like Us reveal his mastery in combining music and literature. But even in these projects, Lo remains, for the most part, a composer first, collaborating with others on theatrical and visual elements. By contrast, Steen-Andersen famously insists on doing everything himself, patches, videos, designs, electronics, as well as the music, of course. Lo’s foray into audiovisuality may thus feel a little out of character, a kind of experiment, perhaps even an act of homage. Yet I commend the effort. Often it is precisely by imitating our idols that we discover new paths, daring to venture into the unknown. Mastery comes through repetition and experimentation, until ideas ripen into maturity. And indeed, there is a certain vulnerability in Lo’s aesthetics that shines through here, a willingness to leave only the thinnest threads of sound, weaving them into a spider-like web of music. This demands a different kind of boldness, one that contrasts sharply with Steen-Andersen’s almost overconfident theatricality, and reveals Lo’s nuanced sensibility, which always places music itself at the centre.

While the outline of the two pieces was strikingly similar (instruments surrounding the audience, video projection at the front), what followed in Steen-Andersen’s Black Box Music (BBM) was, by its dramaturgy and flow, an entirely different beast. First premiered in 2012 at Darmstadt, BBM is one of the works that propelled the (then still young) Danish composer into international prominence. The fact that last week’s performance was already the 75th speaks volumes about the allure of Andersen’s mischievous style within the new music community, especially given how the notoriously fast-paced art world tends to crave endless novelty, only to discard its “babies” after one or two outings.

While the piece has a distinct multimedia character, as Andersen himself noted in the post-concert talk, there is no actual “high technology” involved, neither from the perspective of 2012, nor even less so today. What makes it remarkable is the simple but clever conceit: zooming in on the conductor’s hands and isolating them inside a box, much like an experimental vitrine for chemicals, projected onto a massive screen. It is a strikingly fresh angle, especially in the early 2010s, when the demand for artistic austerity often left little room for the kind of playfulness that BBM openly revels in.

Scored for 15 instruments (arranged here in three blocks of five players around the space) and a percussion soloist in front of the audience, his hands hidden inside the amplified “black box,” the piece demonstrated the virtuosic coordination of the HKNME and their guest percussionist Rodrigo Maqueda. Originally from Spain and now based in Basel, Maqueda describes himself as a heterodox artist moving between experimental art, electronic music, and club culture, with numerous solo projects that integrate percussion virtuosity, electronics, and light into immersive experiences. This heterogeneity of talents served him well in BBM, where he fused visual gesture and sonic signal with Swiss-clock precision, navigating constantly alternating groupings of 2, 3, and 4, along with sudden tempo shifts, which the HKNME piously followed (albeit with the help of a click track).

The piece begins dramatically: Maqueda’s hands part the curtains, unleashing a grand conducting gesture that triggers a loud, sustained tutti chord, only to snap shut again. This opening alternation of action and denial makes it clear that we are entering a theatre of the absurd, grandiose gestures collapsing into irony. From there, the piece slips into persiflage, venturing into “Mickey-mousing” territory, where hand signs trigger cartoon-like sonic effects. A “talking hand” gesture elicits wah-wah brass, a finger pistol sets off a whip crack, a phone-hanging signal coincides with a clipped piano pling. It is a Tom & Jerry world, delightfully ironic, especially in contrast to the gravity of Andersen’s older contemporaries like Marco Stroppa, Wolfgang Rihm, or Mathias Spahlinger.

It also marked a generational turn. Around that same Darmstadt edition, the focus on Cage was juxtaposed with younger voices like Jennifer Walshe, Stefan Prins, and Johannes Kreidler, composers who, like Andersen, cared less for pure sonic craft and more for the interplay of sound with visual elements, perception, and presentation format. BBM fit perfectly into that ethos. And yet, here lies my greatest critique. While the performance was faultless (Maqueda’s gestures crisp, the ensemble tight and passionate), I left with a nagging sense of absence. My memory of discovering this piece years ago was that of a revelation. As a student in Stuttgart, it struck me as a breath of fresh air against the heaviness of both my peers and the “established” masters. Later, during my doctorate at Stanford, I even included it as one of my self-chosen works for the qualifying exam. It was, for me, proof that farse and play could coexist with artistic rigour.

Hearing it live at last, 13 years later, was a different experience. Perhaps the vastness of Kowloon West’s Freespace, which demanded stronger amplification, dulled its impact. Was it the idealised memory of high-quality recordings contrasted with the natural imperfections of live performance? Or perhaps my momentary state of mind, my ears more experienced, and my expectations more demanding? The first ten minutes still charmed me with their humour, but after that, the surface quip seemed unable to deepen.

The middle section, with its resonating pitchforks, strings sustaining microtonal oscillations, and the plucking of rubber bands (later struck by a motorized ventilator), felt ingenious but, for me, slightly forced. The subsequent actions (balloons, cups, party streamers, electric fans) were always timed with Andersen’s masterly sense of dramaturgy, each arriving just before the previous idea wore thin, yet the whole remained locked in a “what you see is what you get” logic. For all its wittiness, the sonic vocabulary never truly expanded.

By the last 15 minutes I felt disconnected. Not bored—Andersen’s pacing is too precise for that—but unsatisfied, as if the piece’s greatest strength (its tight audio-visual amalgamation) had become its limitation. The cleverness of its sonic cues, so striking at first, began to fade into predictability, much like the sound of collecting coins in Super Mario, thrilling at first, only to quickly disappear into the background of habit. Given the large ensemble and extended techniques, one longs for some imaginative deviation, some unexpected drift towards a new sonic alloy, but it never arrives. This is not to deny Andersen’s achievement. The dramaturgy is flawless, honed over dozens of revisions (until, as he said, his publisher begged him to stop revising). The work remains powerful and enjoyable, even if, in 2025, it starts to feel slightly dated. While its perky nature anticipates TikTok-like short-attention gimmickry (which did not yet exist at the time it was written), its 45-minute span betrays the very new generation it seems to prefigure, clinging instead to the older generation’s belief that a piece must carry weight, even if through its length alone. The mismatch between its lightness of material and heaviness of form perhaps explains my ambivalence.

Still, in a field crowded with works lacking joy, craft, or sonic clarity (and God knows I paid my dues listening to hours of such concerts), Black Box Music remains a masterstroke. It proves that great art need not rely on “great material,” but on insightful concept and knife-sharp execution. It shows how a whole world can be built out of play, how childhood imagination, free of fear, rules, and correctness, can create something both simple and profound. I will always remember this piece as one that blew my mind when I was very young, and one that convinced me that contemporary music was still alive, worth pursuing, worth digging into. Even if my experience of it today was more tempered, I remain grateful to Maestro Andersen.

Summing up HKNME’s new season opener under the theme of GAME/PLAY, we see a particular interest in new forms - right from the ensemble layout, compact formats - a short, tightly curated concert under an hour, a focus on multimedia, and the curation of works which, judging by the sold-out tickets, enthusiastic applause, and engaged post-concert discussion, resonated strongly with a predominantly young audience. Connected conceptually yet strikingly different in execution, Antiphon and Black Box Music offered, on the one hand, vulnerability and delicate exploration, and on the other, spectacle and theatrical wit. Together, they displayed a spectrum of contemporary music that combines savoir-faire with carefree experimentation, reaching both seasoned connoisseurs and curious newcomers. The promise of more exciting concerts to come is clear, and we can eagerly await the rest of the season.

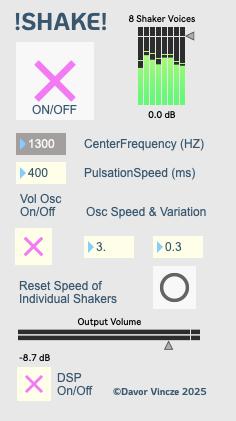

!SHAKE! is out - a physical model of a shaker. Go and test it out! Instead of browsing for hours looking for various shaker recordings online, you can now make shaker of any timbre & speed that you might need for your piece. Download HERE!

About !SHAKE!

!SHAKE! is a physical model of a hypothetical shaker. It begins with a white-noise signal, which is shaped by a bandpass filter centered around a user-defined frequency with subtle variations. The patch generates eight independent voices of this filtered noise, each with a slightly different center frequency and delay, thereby simulating the sound of multiple grains inside a shaker such as a maraca, caxixi, or egg shaker. The duration of one cycle is set in milliseconds. Each cycle consists of two shakes: the first reaches maximum intensity, while the second is slightly softer, imitating the natural motion of a shaker with an initial action followed by a rebound as the hand moves back and forth. Within this continuous flow, the noise~ object is interrupted by the train~ object, whose constant oscillation models the chaotic behavior of many grains moving at once. A BANG button allows the process to reset to a new set of random values. Additional realism is introduced through two cycle~ oscillators, which modulate dynamics between 0 dB and –15 dB. This recreates the small, natural fluctuations in loudness typical of a human performer. In short, rather than searching for recordings of different shakers, !SHAKE! allows you to generate a convincing digital imitation, controllable in frequency, speed, and dynamic variation, offering a flexible and natural-sounding alternative.

Composer, Researcher, Curator of Contemporary Music

Maison ONA info@db-vincze.com

Site by Daniel

Composer, Researcher, Conductor of Contemporary Music